Using Targeted Review to Improve Study Efficiency

Published 02-21-2024

Targeted Review is a weekly review session that focuses on a specific set of study material. It’s a study technique that:

- Helps make your notes effective for understanding advanced concepts

- Helps study efficiently by removing time sinks or notes that aren’t valuable

This technique is based on content from Doctor and Study Coach Justin Sung. - Targeted Review by Justin Sung

What Should I Be Reviewing?

Targeted review is generally used for flashcards and note taking apps that have flashcard-like qualities.

- Highlight any notes / flashcards you’ve marked easy multiple times

- Highlight any notes / flashcards you’ve marked hard multiple times

Automating Highlights

Flotes is a note-taking application that lets you study notes like flash cards. It enables Targeted Review by highlighting repeated easy / hard feedback automatically. [1]

Starting our Targeted Review

Once you have a curated list of notes, materials or flashcards. We can significantly improve the effectiveness of those notes, and the efficiency of our future study sessions.

What do I do with the Easy Notes?

Two options for handling easy notes / flashcards

- Archive or otherwise remove the note from future study sessions

- Combine that note with another note to form higher-order questions

🖥️ Example

This example uses a concept from computer science known as Inheritance and Composition. But to be clear, targeted review is not specific to computer science.

Imagine you have two notes, that challenge you with a question, to gauge your retention. Both questions are fairly easy because they’re checking if we can recall the definition of some vocabulary.

BLANK allows programmers to create classes that are built upon existing classes,

to specify a new implementation while maintaining the same behaviors (realizing an interface),

to reuse code and to independently extend original software via public classes and interfaces.

[Source](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Inheritance_(object-oriented_programming)And

BLANK is about combining objects within compound objects, and at the same time,

ensuring the encapsulation of each object by using their well-defined interface

without visibility of their internals.

[Source](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Object_composition)Ideally, both of these questions become very easy, relatively quickly. We can significantly improve these two notes by aggregating them into one higher-order note. i.e. A note that helps us build understanding or the ability to apply a skill. Rather than just regurgitate definitions.

Two examples of more challenging questions

In general, BLANK is preferred over BLANK, why?OR

// The following code is using BLANK. How do you know?

class Queue<T> {

public length: number;

private head?: Node<T>;

private tail?: Node<T>;

constructor() {

this.head = this.tail = undefined;

this.length = 0;

}

peek(): T| undefined {

return this.head?.value;

}

// ...

}These notes can help us build and understanding of the broader topic (or help us recognize our lack of understanding 😅). What I enjoy about this process is that I iterate or build-up to better notes. When I become hyper-focused on taking the perfect note (lol) I tend to waste time over-thinking how to make it perfect.

This is a fairly idealistic scenario, but it helps get the idea across. In reality, you may have just 1 overly easy note that you connect to another concept. Regardless of if you have a matching “easy” note / flashcard for that concept.

What do I do with the Hard Notes?

Three options for handling hard notes

- If it’s difficult to remember because it’s not worth remembering, pitch it.

- Breakdown that note / flashcard into multiple easier chunks

- Connect that note to existing knowledge or analogies to aid understanding

This section could be it’s own set of articles. So we’ll try to keep it (relatively) short. Our goal is to connect the main idea / concepts in the note with prior knowledge, creating networks of relationships.

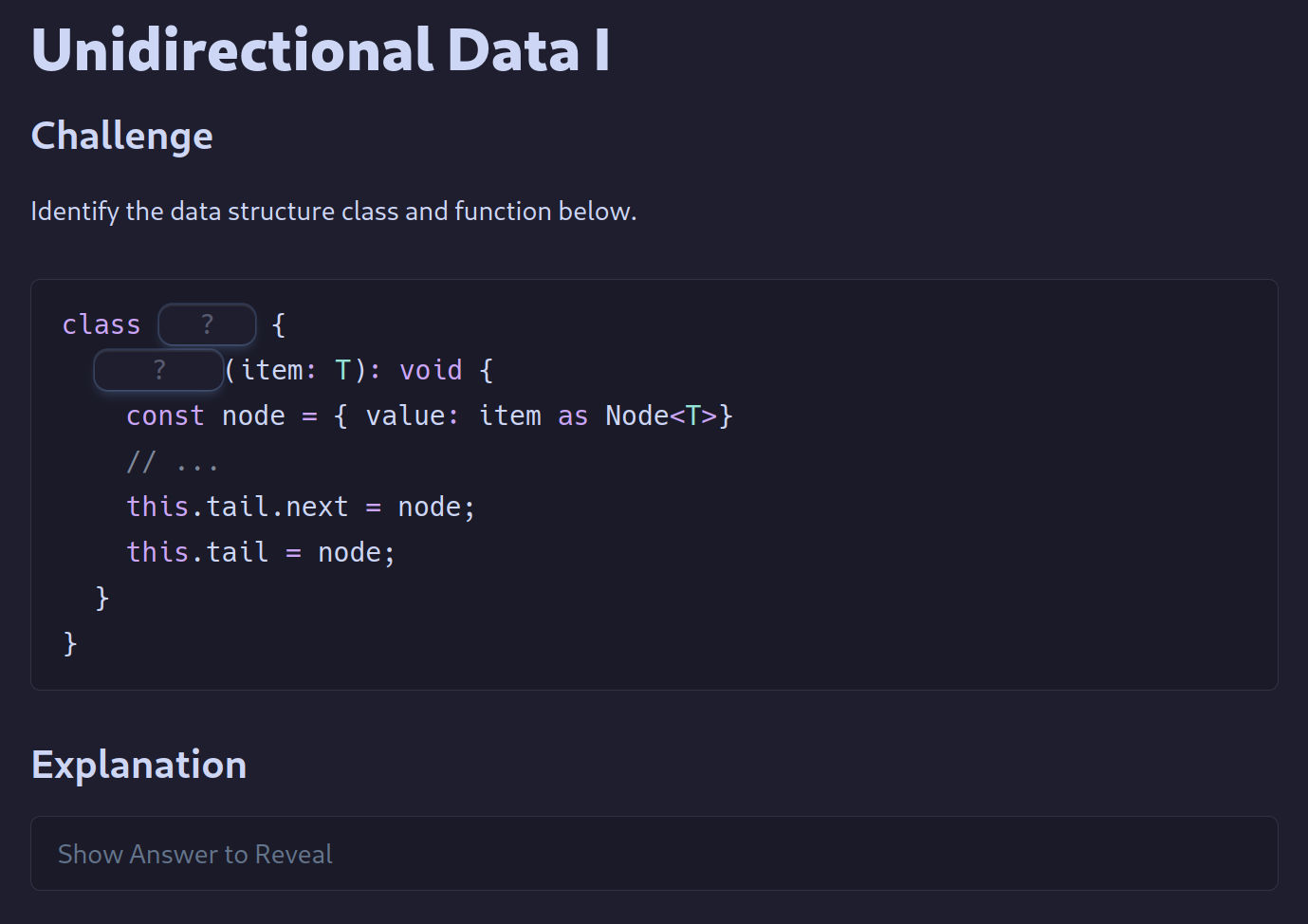

🖥️ Example

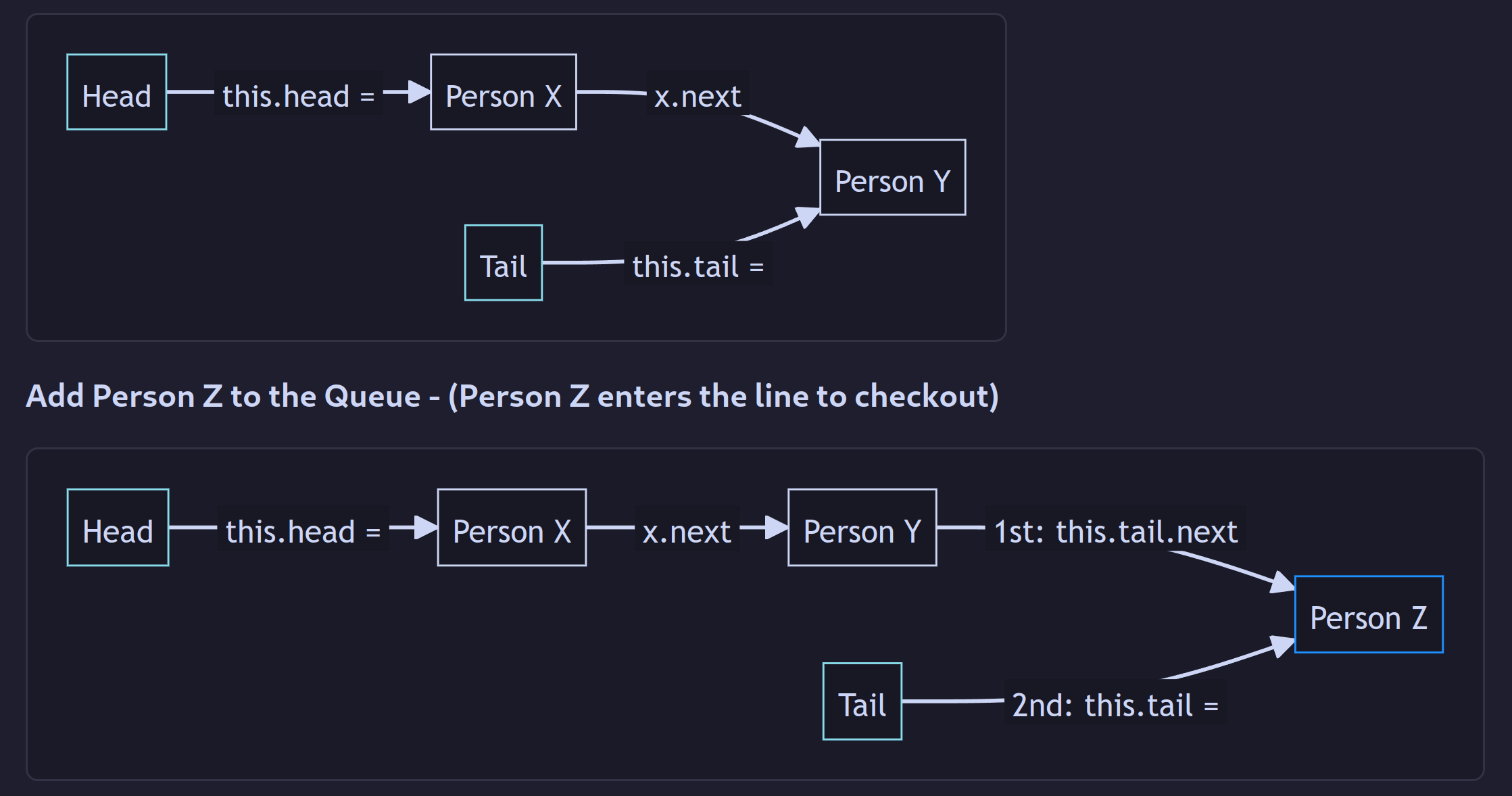

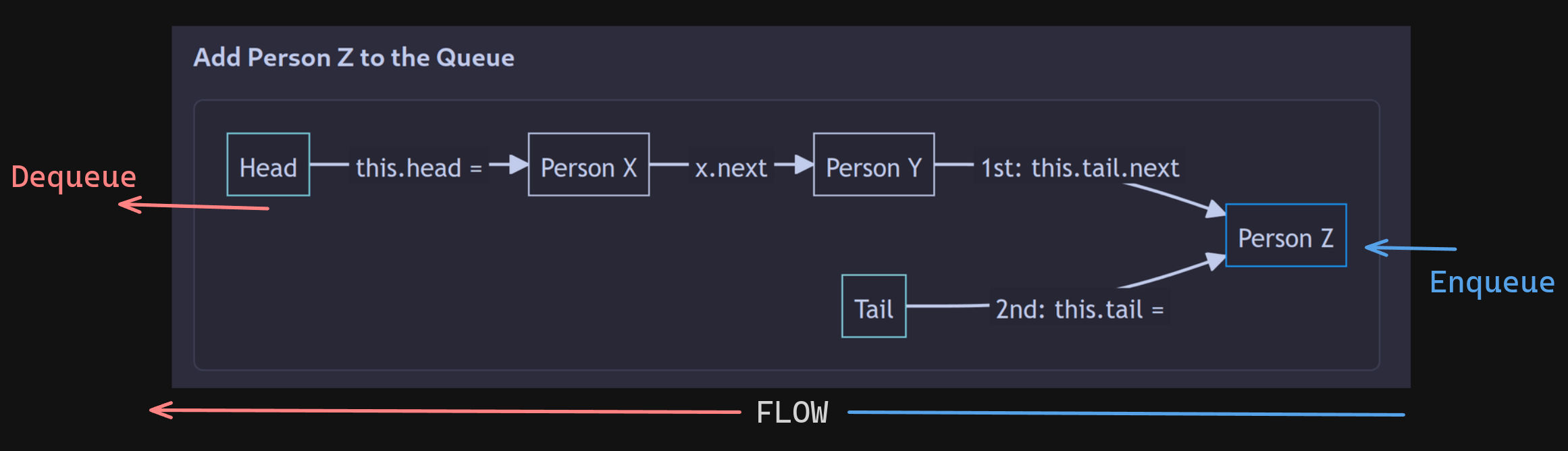

Let’s say we’re trying to learn data structures. We’re struggling with identifying Stacks versus Queues by reading code.

- The answers are Queue (which is First in First Out) and enqueue (which means add to the queue)

class BLANK_1 {

BLANK_2(item: T): void {

const node = { value: item as Node<T>}

this.length++;

if (!this.tail) {

this.tail = this.head = node;

return;

}

this.tail.next = node;

this.tail = node;

}

}We can connect this new concept to existing knowledge by creating an analogy to something we already understand. For example, a Queue in Computer Science can be thought of as a line of people checking out at the grocery store. Additionally, we can condense down any wordy explanations into a flow-chart of our analogy. This is a notable improvement because:

- Explaining the concept with an example

- Using an analogy to connect to something we already have knowledge of (a line of people)

- Using spacial & visual elements to improve our ability to chunk and encode the information

I’m confused, I don’t understand the flow-chart

The queue example (even if you don’t know computer science, you’re probably familiar with grocery store lines) is one of my favorite examples of amplifying understanding through existing knowledge. Because, sometimes, it backfires 😅.

The code for the Queue adds new nodes to the queue via the tail (what would be the end of the line in our analogy). Thus, the arrows point towards the “back” of the line.

Painfully obvious, but in the real world, we generally follow arrows pointing to the front of the line. And, in flow-charts, arrows generally indicate the flow or direction of the data.

But, our chart is not wrong. It’s just that those arrows represent the node’s next value. Not the direction that people exit the queue. Even though existing knowledge is without a doubt one of our most powerful tools for learning. It can also hinder us in some cases. When scenarios like this occur, I like to add visual elements or notes to soften these bias.

In this specific example I like to add additional arrows pointing the direction of the enqueue (add) and dequeue (remove). If I’m trying to keep the fill in the blanks challenging, I’ll rename those arrows to something like add / remove so I don’t give away the answer.

Conclusion

Here’s what our final note might look like using fill-in-the-blanks and hidden-blocks!

And with the answers / explanation revealed

If you enjoyed this article, consider checking out Flotes! It’s a study and note taking app that is designed with concepts like this built into it.

[1] - This is a pro feature of Flotes